The instrument sits unassumingly near the entrance to Tew Recital Hall in UNC Greensboro’s Music Building. Many who walk through the lobby might casually pass it by, completely unaware that the trumpet now resting on a plinth once produced some of the most beautiful sounds in recording history. It’s the horn Miles Davis played on Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time.

Having sold roughly 5,000 copies a week since its release in August of 1959, Kind of Blue is deeply engrained in the American psyche. The album has near universal appeal, casting its spell on jazz aficionados, hip-hop connoisseurs, and die-hard rock fans alike. The iconic instrument at the heart of this music isn’t locked away in someone’s private collection. It’s permanently on display in the Triad, accessible to any North Carolinian seeking inspiration or pilgrimage.

UNCG Photo

The story of Miles Davis’ trumpet is a reminder that UNC System institutions and affiliates are much more than classrooms for instruction and labs for research. They are venues and galleries, exhibition spaces and public lecture halls. They are public resources where cultural knowledge is preserved, enjoyed, studied, and promoted.

At a moment when we face unprecedented challenges on many fronts, this work helps North Carolinians understand and appreciate the cultural fabric that weaves us together. It helps us rediscover joy and beauty in troubling times. It sutures division, promotes empathy and understanding, and heals wounds.

Changing the Course of Music History

Musician and UNCG Miles Davis Jazz Studies Program Professor Steve Haines is quick to note that spontaneity is a key element in jazz. Davis, for example, supposedly sketched out his ideas for three of the songs on the album just a few hours before heading into the studio. In a musical form that privileges improvisation and innovation, much can go wrong during a recording session.

“Jazz is very flexible. It’s human. A lot of times jazz fails because the musicians are trying something new. They are risking something,” Haines explained. “But on Kind of Blue, the stars aligned. Davis had brought together the best jazz musicians on the planet for two days of recording. In most other recordings, we hear the potholes, or mistakes, or the risks gone awry. But with Kind of Blue, we have something that’s pretty close to perfection.”

The result, in nearly everyone’s estimation, is one of the most significant masterpieces of 20th century music. Not only is the album a perennial fan favorite. It also changed the course of music.

“Usually art at its highest level isn’t necessarily popular. But, in this case, we have one of the greatest pieces of art that also has mass appeal,” said Haines.

Chief among the album’s innovations is its modal approach to improvisation. Prior to Kind of Blue, jazz musicians largely played standards, and the soloists played to the chord changes driving the melody. A soloist might outline the notes in a chord for only a few seconds before switching to the next. During the bebop era of jazz in the 40s, the chord changes were notoriously complex and speedy.

In modal jazz, melodic structure is stripped down to a bare minimum of chords, giving the soloist more freedom and responsibility for charting the song’s course. “So What,” the instantly recognizable tune that opens the album, is arranged around just two. Davis had already begun experimenting with modal jazz, but this new approach to music became the defining principle on Kind of Blue.

“Davis wanted to remove the hoops of jumping through recurring chord changes. He wanted to slow the harmonic rhythm down. With fewer chord changes, the soloist would have a chance to think more about playing melodically,” explained Haines. “This gave a space and coolness to the music. It simplified the thinking, but not the melodic content. Now the soloist was challenged to come up with fresh sounds, with less predetermined material to work with.”

The Rhythm of Still Photography

Kind of Blue is a singular work of art, but it’s not an isolated one. The album’s innovations and tone reflect some of the broader shifts that were taking place in American and international culture during the late 1950s.

Across the UNC System, students and campus visitors encounter opportunities to discover and study other representative works of art from the same era, each evocative in their own way.

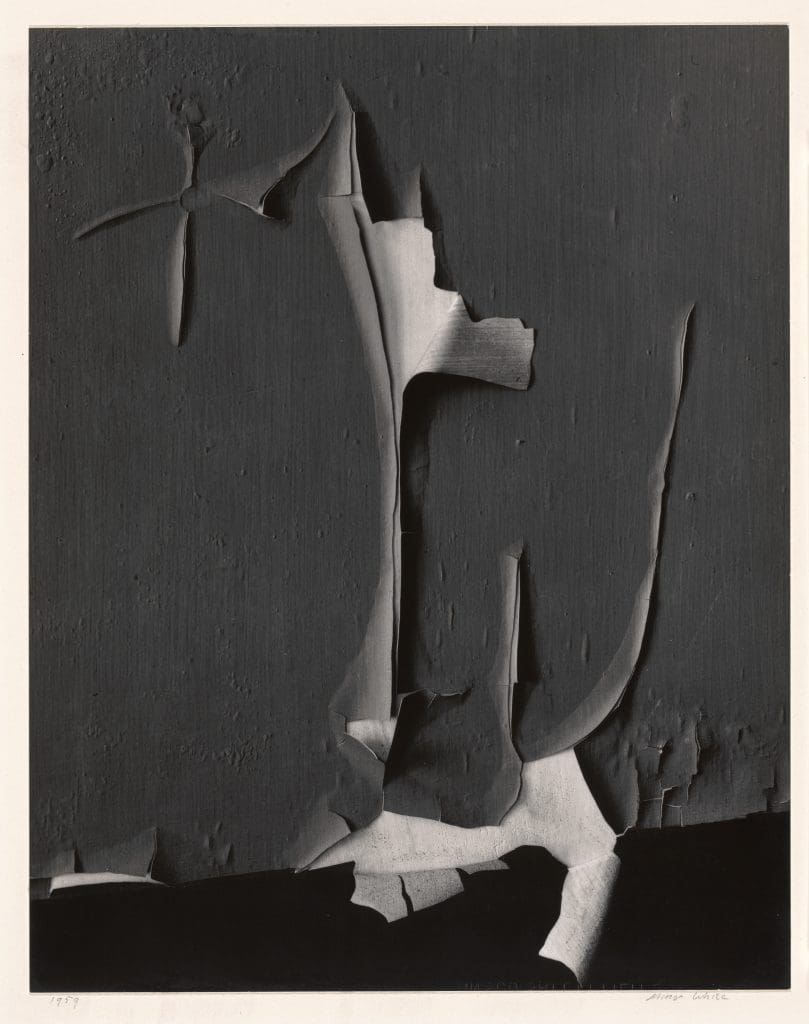

When asked to identify a work in the Ackland Art Museum collection that speaks to Kind of Blue in an interesting way, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs Peter Nisbet thought immediately of Minor White’s Peeled Paint, also created in 1959—a stark, black and white photograph of paint losing its grip on a wall.

Although the photograph doesn’t explicitly represent musicians or a scene inside a jazz club, Nisbet still sees musicality in the image. He points out the rhythms of vertical lines and the play of light and dark dancing from left to right across the image.

“Yes, it’s peeled paint. But it’s also an abstraction, which opens up parallels to jazz. It isn’t illustration or a representation of anything in particular. But it evokes a specific mood, and this is what Davis’ music does,” Nisbet explained.

Dr. Allison Portnow Lathrop, a musicologist and the Ackland’s head of public programs, adds that what may seem to be only a chance encounter with a ‘found” scene is actually a highly composed and consciously rendered view. In the same way, the improvisation of jazz might appear to be totally random, when in fact it is carefully crafted through the use of sonic tools and musical technique.

More than this, Nisbet sees the photograph’s spare visual sensibility as analogous to Davis’ unique approach to music.

“As I started to think about what works we have in the collection that could be seen in dialogue with Davis’ music, I looked for a piece that would be a reaction against the more excessive emotionalism of the Abstract Expressionism of the previous generation of artists, like a Jackson Pollock. The restrained style is perhaps analogous to Davis’ move away from bebop’s baroque sensibility,” he said. “White’s photograph is much more ‘cool.’ It has a restraint, but it also has intensity.”

Although the photograph measures only 9 3/8 inches by 7 3/8 inches, Nisbet believes it has a “monumental” quality. He explains that a trip to the UNC-Chapel Hill’s Ackland Art Museum to see the photograph in person gives visitors an awe-inspiring cognitive and emotional experience that can’t be replicated in online platforms.

“The real object has an aura and a power that a digital image hasn’t got. The quality of the paper, and the luxuriousness of the blacks and the tonality in this particular case. The scale of the original work of art—is it small, is it big?–that’s all part of the experience and part of what the photographer wanted to do,” Nisbet said. “That is key to what the Ackland offers, in the same way that Miles Davis’ trumpet at UNCG has a certain magical quality to it. When you come to a gallery or a museum, you interact with an authentic object. It has texture and details that get lost in the digital image.”

Until the museum can safely welcome visitors again, digital images will remain the second-best but safest way to access this and other works in the collection. Peeled Paint and 25 other works by Minor White can be found on the Ackland website. Visitors can even study an alternative printing of Peeled Paint with different cropping and tonalities, a visual experience akin to enjoying a different performance of the same musical piece.

Nisbet is also quick to add that Peeled Paint, a major work by one of the great post-War American photographers, reflects the level of quality visitors will find throughout the Ackland.

“We have this incredible depth in our collection, representing a wide range of great artists, cultures, and time periods,” he chimed. “You can mention practically any major work of art, historical event, or significant issue, and the Ackland has a work that responds to it in some way. If you have an interest in, say, Miles Davis’ trumpet, you’ll find something here that expands on the conversation.”

Exploring the Fusion of the Arts in the Classroom

To state the obvious, art isn’t just for exhibition spaces and performance halls. It’s also a vital part the learning experience. At every UNC System institution, students fill classrooms to learn the importance of thinking critically about works of art. Through instruction, students become more cognizant of how they are responding to creative expression, and they learn to recognize the techniques and cultural contexts that provoke these responses.

At UNC Wilmington, Dr. Juan Carlos Kase, jazz historian and film studies professor, teaches courses on the histories of avant-garde and independent cinemas. His students learn that the late 1950s was a particularly exhilarating time in the American film scene, in large part because cinema, jazz, literature, and other visual arts were all influencing one another.

Two years before the release of Kind of Blue, French director Louis Malle hired Davis to record the soundtrack to the crime film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows). Instead of composing a formal score, Davis took the highly unusual step of improvising on the fly. He assembled a group of musicians, gave them a few chords to work with in advance, and then they played spontaneously along with the film, responding to the action and the mood unfolding onscreen.

Davis would push this approach to its culmination in Kind of Blue. According to Kase, Davis’ output during this period exemplifies how jazz was becoming more cinematic by the late 1950s—evoking moods that might shift over the course of a single composition in ways that ragtime, swing, and bebop hadn’t in the early decades of jazz history.

At the same time, the cinema was also embracing the improvisational aesthetic of jazz.

“Jazz music historically has been based on the popular song book—on Broadway show tunes. That changes in the late 1950s. That means there’s an untethering from conventional pop songs,” explained Kase. “And you have something similar happening in the cinema, where you see art cinema directors untethering themselves from the tight narrative structures of conventional Hollywood entertainment. You have a new spontaneity in both independent cinemas and in jazz.”

The influence of jazz proliferated in European art films, such as Elevator to the Gallows and, even more notably, Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de soufflé (Breathless, 1960).

In the United States, actor and director John Cassavetes’ directorial debut—a landmark independent film called Shadows (1959)—featured a score by jazz bassist Charles Mingus and famously concluded with a title card stating, “The film you have just seen was an improvisation.”

Jazz even started to have a more significant impact on mainstream Hollywood cinema, as evident in Duke Ellington’s groundbreaking score for Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959).

“This was an important moment. It’s the first time an African American had done the soundtrack for a big Hollywood movie,” explained Kase. “Ellington appears in the film, sitting next to Jimmy Stewart playing the piano. It’s a remarkable moment, when the Hollywood establishment overtly recognizes Ellington’s genius.”

“Musically and cinematically, this was a very different type of collaboration than what Davis and Malle pursued. But both films demonstrate how jazz and cinema were feeding off of one another, responding to a special moment in the late-1950s in which they were increasingly recognized as art forms – akin to painting and poetry – rather than varieties of commercial entertainment.”

Weaving Together Past and Present

Mid-century literary works certainly abound on course syllabi. Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Langston Hughes’ Selected Poems, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, to name a few, were all published in the late 1950s. All are staples in UNC System classrooms.

bryon d. turman, author and lecturer in the Department of English at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, teaches two popular classes on hip hop. While the courses focus on contemporary music, turman begins the semester by asking students to read an influential essay by poet and critic Amiri Baraka: “Jazz and the White Critic,” published one year after Kind of Blue’s release.

In the essay, Baraka argues that jazz and the blues were historically dismissed as unsophisticated and in “bad taste.” Because the vast majority of critics writing at the time came from a background in Western classical music, where every sound is planned ahead and written down, they did not have a framework for evaluating and understanding the significance of a genre rooted in improvisation, nor did they grasp the influences that shaped jazz’s distinctive sounds and structures.

turman uses Baraka’s ideas to illuminate the critical response hip hop faced in the 1980s and 90s as its popularity blossomed. A multicultural musical phenomenon born on Bronx street corners and parks, hip hop is rooted in the aesthetics of spontaneity. As with jazz in the first half of the century, hip hop was similarly dismissed as being non-musical or, worse, reviled as a threat to American cultural norms.

turman uses this backdrop to establish a foundational idea for his course: no one can fully grasp the significance of Black American music without understanding its influences, and no one can fully appreciate contemporary hip hop without reckoning with the influence of jazz.

“Black art is often critiqued using a European standard, which doesn’t speak to the people who make or consume the music,” explained turman. “When it comes to Black music, the critic often lacks that historical perspective. For many, Black music seems to exist in a silo. Jazz comes and it’s a new thing. Funk comes and it’s a new thing. Hip hop comes and it’s a new thing. It’s important for all of us to understand that there’s a lineage there that weaves these movements together … and which has an immeasurable impact on American culture writ large.”

“I want my students to see that rap is an extension of jazz. You can hear it in the samples of jazz classics used by hip hop pioneers like Stetsasonic and A Tribe Called Quest. You can hear it in the rhythmic da-dat, da-dat, da-dat recitation of lyrics that is so central to the genre,” he said.

turman’s ideas illustrate the broader significance of keeping Miles Davis’ horn on display at UNC Greensboro: our institutions’ work to preserve, study, and promote historical art forms and culture does much more celebrate the past.

It helps us make sense of the present.

Celebrating the Public in Public Higher Education

The story of how Miles Davis’ trumpet landed in UNC Greensboro’s Music Building isn’t just a celebration of the arts. It is also a reminder that North Carolinians themselves are the primary investors in our institutions.

Arthur “Buddy” Gist was a North Carolina native. In fact, his brother Herman served in the legislature for more than a decade. Gist moved to New York City, where he became a prominent business man. He hosted parties for the Kennedys and palled around with the likes of Sydney Poitier and Harry Belafonte.

Extroverted, funny, and charismatic, Gist had no difficulty making friends. He met Davis at a gig, and the two became tight. When Davis went on tour, Gist tended to his children. When Gist founded his Kilimanjaro African Coffee business, Davis invested … and even named his album Filles de Kilimanjaro after the venture. As a token of this friendship, Davis gave Gist the horn that changed history.

Gist eventually returned to his native North Carolina. He had left New York City, but he hadn’t lost his charisma, his generosity, or his prized material possession. Eventually, he became friends with the faculty and staff in UNC Greensboro’s School of Music, who gobbled up his larger-than-life tales of running with so many jazz legends.

Gist could have easily sold the instrument and lived the remainder of his days in comfort. Instead, he opted to support higher education.

Haines paraphrased Gist’s generous rationale:

“Buddy would say to me, ‘Mr. Davis would have wanted it to go to a university. Mr. Davis believed in education. If I sold the trumpet, it would be gone … sitting in someone’s house. What good would that do? But if it’s in a place where people can enjoy it. Where it can inspire. That’s where it should be.’”

Gist passed away in 2010, but his generosity continues to impact the university. The gift initiated a conversation between Gist, the university, and the Miles Davis estate, which eventually gave UNC Greensboro exclusive rights to use Davis’ name for its jazz studies program. Gist hadn’t just given the university an object. He had given it prestige and visibility.

Arts in a STEM World

In an era when so much emphasis is placed on the UNC System’s cutting edge STEM research and education, Davis’s trumpet stands as a shining reminder of how the University’s arts and arts education bring long-term cultural and economic value to North Carolina.

“Music and art are especially important at an engineering school like N.C. A&T,” said turman. “I tell my engineering students that the pioneers of math and science … figures like da Vinci and Newton … were also connoisseurs of art. I don’t think that’s by happenstance. You can talk about the music in math. There’s art in a calculus formula. Physics isn’t just describing the physical world; it’s the ideas we have about the physical world … and those things are creative.”

“Conceiving of E = mc2 doesn’t happen unless you’re thinking outside the box. Understanding music, art, and language enhances creativity in all fields.”

bryon d. turman, author and lecturer in the Department of English at N.C. A&T

Through exhibits, festival programming, research and publishing, community outreach, and coursework, UNC System faculty, staff, and students generate, curate, and study works that inspire, provoke, broaden horizons, and change our world.

In times of crises and hardship, this work isn’t less relevant. It’s more important.