UNC SYSTEM GIVES NC WINE INDUSTRY ITS LEGS

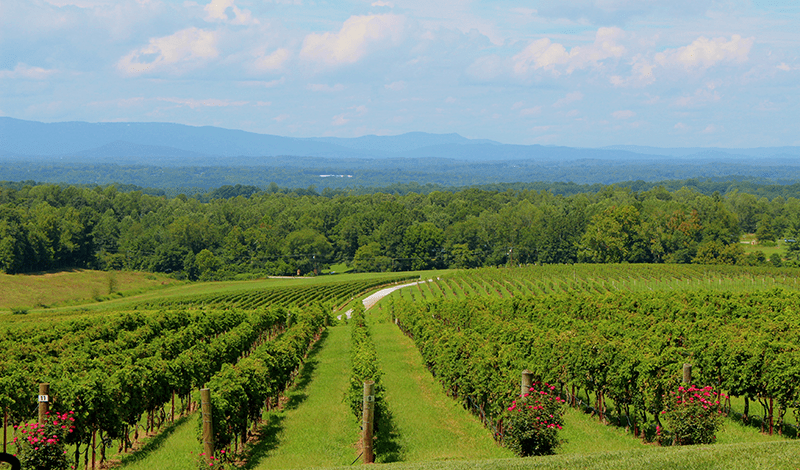

Imagine yourself relaxing on a terrace. Beyond the perimeter of shade, the midday sun beats down on acres upon acres of trained grapevines. A sommelier hands you a glass of Montepulciano to sample. You savor the bouquet and gently swirl the glass, watching the wine’s legs cascade down the sides of the glass. Crickets chirp the afternoon away. A fountain gurgles in the background. Gazing out into the distance, your eyes trace the narrow ribbon of asphalt that winds lazily between the rolling hills, leading from this vineyard to the next, and the next, and the next.

You could be in Tuscany … but you don’t have to be. This pastoral setting could just as easily sit far closer to home, in North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley, the state’s first federally approved American Viticulture Area. More than three dozen wineries dot the landscape in Surry, Yadkin, Wilkes, Davie, Davidson, Forsyth, and Stokes counties.

North Carolina wine has certainly matured, and it is helping to revitalize rural economies once dominated by tobacco. With nearly 200 licensed wineries and 2,300 grape-bearing acres, the state now ranks seventh in the United States in terms of wine and grape production. A 2016 economic impact study estimated that North Carolina’s wine and wine grape industry generated $375 million in wages and $89 million in state taxes.

In various ways, UNC System institutions have helped to grow this increasingly important segment of the state’s economy. The research and talent coming from constituent institutions contributes to every stage of wine production and sales, helping growers, vintners, marketers, and hospitality workers uncork the full potential of the state’s grape yield.

NORTH CAROLINA’S WINES, FROM MANTEO TO MURPHY

When Erskine Bowles was president of the UNC System, he pushed each institution to break down the silos dividing the universities and local industries. Although UNC Greensboro’s Bryan School of Business and Economics had always prided itself on being community oriented, the school’s Executive in Residence Sam Troy took on the responsibility of brainstorming new ideas for how faculty and students could engage local industries within the university’s service area.

As it would happen, on a whim, Troy decided to attend a wine release celebration hosted by Raffaldini Winery in Wilkes County. Troy was blown away by the quality of the product, by the passion of the staff, and by the size of the attendance for the event. He realized two things at that moment: that North Carolina could produce high quality wine and that there was a real interest cultivating this industry in the state. He had a hunch that “maybe, in the years ahead, NC really was going to become a player in the international wine industry.”

Two weeks later, when Troy’s now former dean, Dr. James Weeks, asked where UNCG should be concentrating its energies to help support local industry, Troy identified two conventional choices (aviation and high-tech textiles) and a wild card: wine. At the time, well over half the vineyards in the state were within the 120-mile radius of the university’s service area. Not only would the wineries benefit from the school’s input, but students would have easy access to immersive learning experiences and professional opportunities. The dean embraced Troy’s idea, and thus began a rigorous partnership between UNCG and North Carolina winemakers that has thrived for 13 years.

UNCG’s work reflects the scale of North Carolina’s wine industry and its vast impact on the state’s economy. The industry encompasses far more than the business of growing grapes. It also depends upon and contributes to a number of secondary and tertiary industries, including glassware, design (to make labels, for example), and hospitality and tourism. One glance at the university’s impressive tally of engagement efforts makes it obvious that faculty and students are having an impact across the spectrum of these business interests.

To date, the Bryan School has completed 19 industry studies and projects, including a comprehensive five-year industry strategic plan, marketing analyses, a benchmark study measuring the effectiveness of tourism signage, a smart business practices resource, and an online training program for tasting room managers. They have also actively participated in the North Carolina Fine Wines Competition.

This work isn’t limited to the Yadkin Valley region. Winemaking is a statewide endeavor. Today there are five American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) in the state, and the Bryan School team works with wineries from Murphy to Manteo.

“Our team has visited roughly 130 different wineries across the state,” Dr. Erick Byrd, director of the Bryan School’s Center for Industry Research and Engagement, explained. “Many of these are located on old tobacco farms in very remote, rural locations, so we can see firsthand how this industry has the potential to make significant contributions to North Carolina’s economy.”

Making wine requires a significant commitment of time and resources. By some estimates, a winery needs money to stay liquid for ten years before it begins to make a profit. The research coming out of the Bryan School has provided critical support to an industry that requires long-term vision.

“The Bryan School is our secret weapon, and they have been a huge asset in providing us with solid, unbiased information that allows us to identify problems and make long-term, sound decisions,” said Larry Cagle, owner of WoodMill winery in Vale.

This work doesn’t just benefit the industry. It provides invaluable learning and research opportunities for UNCG students and faculty as well. Undergraduate hospitality and tourism students have completed capstone projects working with wineries in Surry County. When the university co-sponsors the North Carolina Fine Wines competition, through the leadership of Tiffany Reynolds, lecturer in the Department of Entrepreneurship, Hospitality, and Tourism, students work the venue and learn what it takes to run the back of the house. Faculty and graduate students collaborate on rigorous, multidisciplinary research in geography, marketing, hospitality, supply chain management, and information systems.

“Our partnership with UNCG and the Bryan School has been very rewarding for everyone involved,” said Dan McLaughlin, founding board member of the North Carolina Fine Wines Society and co-owner of CLINNEAM LLC, a company that provides research, technology, and marketing support for the beverage industry. “The students who work the Fine Wines Competition get real world experience organizing a world class event and an opportunity to network with our Advanced Level III Sommeliers. At the same time, our competition benefits from the Bryan School’s oversight and validation of the scoring process. Their work ensures the transparency of our competition to the industry.”

Notably, three UNCG MBA graduate students, working under the guidance of Sam Troy and Dr. Bonnie Canziani, assistant professor in the Department of Entrepreneurship, Hospitality, and Tourism, won the 2014 Small Business Institute’s Project of the Year Award for the business plan they completed for Raffaldini Winery as part of their capstone project. Owner Jay Raffaldini, who has sponsored several of the Bryan School’s project initiatives, cites this award as tangible evidence of the quality of the talent that flows into the industry from the UNC System.

“I’ve sat through a lot of presentations from students in top business schools—Harvard, Yale, Wharton,” he said. “The Bryan School students’ presentation of their business plan stood up against anything I’d seen before. My hunch was validated when they won a national award.”

Dr. Erick Byrd offered an even more sweeping proclamation of the long-term value of the university’s collaborative relationship with the industry.

“Our work leads to victories on many fronts. Students win–they get experience and they get jobs. The business school and UNCG win, because this work enhances our national reputation. Faculty win, because these partnerships open doors to so many fruitful research opportunities. And local industry wins, because we supply high quality talent and research,” he said proudly.

FROM THE GROUND UP: NC STATE AND VITICULTURE

UNCG’s work concentrates largely on the marketing and consumer end of the industry. But the business of a vineyard begins long before the product gets bottled and tourists arrive at the tasting room. Research and extension initiatives coming out of North Carolina State University’s Department of Horticultural Science get the industry growing from the ground up.

Dr. Mark Hoffmann is NC State’s small fruits extension specialist. Much of his work focuses on supporting the state’s viticulture—the science of growing grapes used in wine.

“The thing that makes North Carolina viticulture so fascinating is the diversity of grapes grown here,” Hoffmann explained. “North Carolina is probably the most diverse state in terms of grape varieties. California might be more famous for its wine, but we actually grow more types of grapes.”

Most North Carolinians are readily familiar with the muscadines that are indigenous (and relatively unique) to the Southeast, which are used in the sweeter wines produced in the eastern part of the state. While many might associate North Carolina more with beer than with wine these days, NC is actually one of the few states with a long-standing tradition of growing grapes for wine. Before prohibition, North Carolina was home to more wineries than any other state, thanks to the abundance of this hardy, native fruit.

Since the 1980s, however, more and more growers have been steadily experimenting with non-native grape varieties of the sort traditionally used to make Italian and French wines. This has introduced remarkable complexity to North Carolina’s winemaking tradition. This variety ensures that consumers today, no matter their taste preferences, will have no trouble finding a North Carolina wine that pleases the palate.

“In most cases, wine-making regions are known for a particular grape. Napa is known for the cabernet, Sonoma for the zinfandel, Virginia for the viognier. North Carolina doesn’t have that singular grape that defines what we do,” said Jay Raffaldini. “Montepulciano and vermentinos do well here, but I have been fascinated watching every vineyard try to figure out what makes them unique. Of course, what grows well in the mountains is not going to grow well in the coast. From a customer standpoint, this is really interesting. You go to Napa, and, after two stops, you’re weary of cabernets. But the diversity here means that every stop in North Carolina is different.”

Much of NC State’s extension efforts have been dedicated to supporting this diversity. In addition to producing, compiling, and sharing the latest research that will help increase yields, Hoffmann and his team have organized forums and meetings that bring together muscadine, bunch grape, and table grape growers. This has nurtured a spirit of collaboration across the state, which Hoffmann sees as vital to the industry’s growth.

NC State also plays a leadership role in distributing scholarly expertise across the state. The university is developing extension teams specifically so that agents are better prepared to help vineyards grow capacity. The university has also helped community colleges develop their own viticulture and enology programs. One notable example is NC State’s collaboration with Surry Community College, which now houses the Shelton-Badgett NC Center for Viticulture and Enology and a research vineyard, which NC State uses for field trials.

“Our goal is to make North Carolina a recognized wine-growing region, and that’s not possible if you don’t have unity,” Hoffmann said. “Viticulture is challenging, and it’s more expensive to grow grapes here than it is in dryer climates, but the people are very engaged. We have a community that’s willing to work together, which is exciting and especially important, given the diversity of species that are being grown.”

THE KICK IN THE BOTTLE: APPALACHIAN AND ENOLOGY

Viticulture is the science of growing the grape; enology is the science of what comes next. When it comes to transforming fruit into something more sublime, North Carolina vintners turn to Appalachian State University’s A.R. Smith Department of Chemistry and Fermentation Sciences for support.

The department’s state of the art facilities directly serve local winemakers in two ways. Its Enology Services Lab—established in 2009 from a U.S. Small Business Administration grant and later expanded with the help of a Golden Leaf grant—offers grape and wine analysis. These services provide winemakers across the state with the product information they need to compile on a seasonal basis, including details regarding residual sugars, acidity, and alcohol content.

At the same time, the university’s Pilot Plant provides a space for students and entrepreneurs to experiment with production. Smaller craft breweries, wineries, and distilleries often don’t have the capacity to try out new recipes or processes. At the Pilot Plant, they can test innovations before investing in scaled up production.

In addition to its facilities, the university also supplies critical talent to the industry through its fermentation sciences degree options. Homebrewing and winemaking have soared in popularity as amateur hobbies, but Dr. Brett Taubman, director of Appalachian’s Fermentation Sciences Program, emphasizes that Appalachian’s students graduate from the program with a theoretical and experiential underpinning they simply wouldn’t get through self-taught trial and error.

“This isn’t a four year degree in brewing. It’s a very rigorous science degree,” he explained. “Fermentation is a highly technical craft that synthesizes biology, chemistry, math, science, and engineering. Our students don’t even get into fermentation until they’ve had two years of foundational chemistry and biology. The industry is incredibly competitive, and what they want are students who’ve acquired the theoretical and hands-on knowledge that a four-year degree can provide.”

Because Appalachian’s graduates can draw from theoretical comprehension rather than rote memorization, they are well-prepared to fix any number of problems that can arise during fermentation. If the fermentation gets “stuck” or if the flavor seems off, they can pinpoint where in the process things went haywire. Furthermore, alcohol production is an inherently dangerous industry, involving compressed gasses and dangerous chemicals. Because Appalachian’s graduates come to winemaking from a scientific perspective, they understand the safety issues and the critical control points. In short, not only can Mountaineers help ensure the quality of the wine, they can also help prevent injuries on the job.

“The industry understands the value of the talent coming out of Appalachian’s fermentation sciences program. We pretty much have a 100% employment rate following graduation,” explained Taubman. “What we contend with is the industry contacting us, looking for more quality talent. We don’t have enough graduates to fill those positions. This is, of course, a great benefit to our students, because they can pick and choose where they want to go. It’s not an easy degree to get through, but those that do really benefit in the end.”

This demand for talent doesn’t just benefits the students. It also reflects the growth of North Carolina’s wine industry and the value of the UNC System’s support for a commercial endeavor that impacts every region in the state.

MAKING AN IMPACT

In the summer of 2013, The Bryan School of Business and Economics collaborated with the NC Wine and Grape Council to create a five-year strategic plan for the state’s wine and grape industry.

When the plan was implemented in 2014, North Carolina had 125 licensed wineries. Today, North Carolina has nearly 200. In 2009, the annual economic impact of the state’s wine and grape industry was $1.28 billion, supporting 7,600 North Carolina jobs. As of 2019, that economic impact has grown to $1.97 billion, supporting just over 10,000 North Carolina jobs. Between 2013 and 2016, the retail value of North Carolina wine sold grew by 43 percent; wages paid grew by 44 percent; and wine-related tourism expenditures grew by 24 percent.

Wine has once again taken root in North Carolina, and UNC System institutions will continue their work to ensure that the growth continues. To this point, The Bryan School and the NC Wine and Grape Council are about the release the status report following the conclusion of the first strategic plan, as well as a follow up five-year strategic plan.

The benefits of the UNC System’s efforts will certainly have legs, strengthening wine-related agriculture and hospitality and tourism industries across the state.

“UNCG is making an impact on the Piedmont/Triad area and beyond. The wine industry is throughout the state, not just in one pocket,” said Sam Troy. “I’m proud of the fact that, over 12 years, our work has served as a clear example of how the university can help an industry, and how industry can help the university. This brings tremendous value to our students, to the community, and to all of North Carolina.”