While our institutions immerse themselves in finding ways to abate the COVID-19 threat, the remarkable diversity of UNC System research ensures that work to address other potentially life-saving treatments continues.

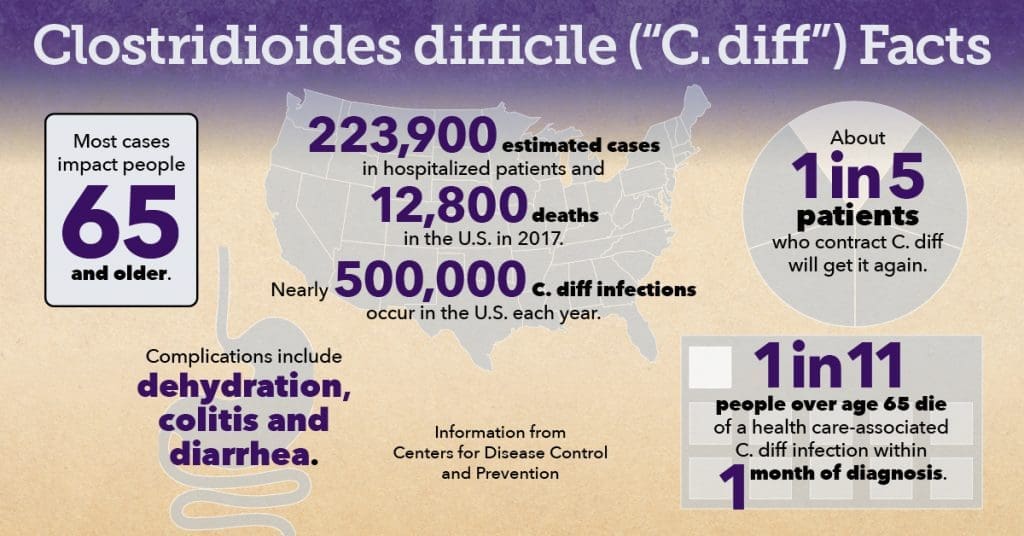

C. diff (Clostridioides difficile) is a case in point. This intestinal bacterium doesn’t grab headlines on a daily basis, but, according to the Centers for Disease Control, it infects more than 500,000 Americans every year. One in 11 of patients over the age of 65 die from health issues related to the infection within a month of diagnosis.

Researchers at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill are testing a potential treatment for C. diff. Meanwhile, an unusual interspecies partnership at East Carolina University is sniffing out new ways to identify and sterilize contaminated sites, preventing the bacteria’s spread in hospitals and healthcare facilities.

Uncovering potential treatments

C. diff threatens human health because it produces toxins that attack the lining of the intestine. The toxins destroy cells, produce patches of inflammatory cells and decaying cellular debris inside the colon, and cause watery diarrhea.

Researchers from NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill, working in collaboration with peers at Pennsylvania State University, have found that a commonly used drug made from secondary bile acids can affect the life cycle of the disease in vitro and reduce the inflammatory response in mice. The findings suggest that this drug may one day be used to treat C. diff infections in humans.

The drug in question – ursodiol, ursodeoxycholate or UDCA – is made by bacteria in the gut and is also FDA approved to treat inflammatory liver diseases. It is currently in Phase 4 clinical trials for use in treatment of C. diff infections.

“If UDCA proves effective against C. diff infection, it would give us an alternative to antibiotic treatments that further disrupt the gut microbiome and can lead to relapse, or to fecal transplants that may have unknown side effects.”

Casey Theriot, assistant professor of population health and pathobiology at NC State and corresponding author of the work

The interinstitutional collaborative research effort looked at UDCA treatment of C. diff in vitro and as a pre-treatment in a mouse model of the disease.

C. diff exists in the environment as a dormant spore. In humans, the spores colonize the large intestine by germinating, becoming bacteria that produce damaging toxins. Theriot and her team, led by former NC State graduate student Jenessa Winston, knew that UDCA would inhibit germination, growth, and toxin production in vitro. They wanted to see if it would have the same effect in a mouse model.

In vitro, treatment with UDCA significantly decreased C. diff spore germination, growth, and toxin activity. In the mouse model, pre-treatment with UDCA had some effect on bacterial growth, but the main effect of treatment was to suppress the inflammatory response of the immune system to bacterial growth and toxins.

“Mitigating the immune response means that pre-treatment with UDCA could significantly reduce tissue damage due to C. diff infection,” Theriot says. “This work is the first to explore how UDCA works in vivo against C. diff infection and demonstrates that the drug may be a viable pre-treatment to help patients avoid damaging effects of a C. diff infection. Our next steps will be to look at dosages and timing, in order to determine how to use it most effectively.”

The research appears in Infection and Immunity and is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R35GM119438). Winston, currently an assistant professor at The Ohio State University, is first author. Jingwei Cai and Andrew Patterson from Penn State, and Stephanie Montgomery from UNC-Chapel Hill, also contributed to the work.

Read the original story and the scientific abstract.

A Canine Collaborator in Healthcare

At ECU, researchers have taken a different tack to combat C. diff: enlisting four-legged expertise to help locate areas in healthcare facilities contaminated by the bacteria.

As a rabbit hunter, Harley the beagle’s future was uncertain. She simply refused to chase down game. Now, the wayward hound has finally found a worthy prey—but not of the woodland variety.

Harley visits Vidant Medical Center in Greenville twice a week to sniff out the C. diff bacterium, which is common in health-care settings and can cause severe intestinal complications for vulnerable patients.

The two-year-old dog partners with Dr. Paul Cook—professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University—to locate the bacterium. With the support of Vidant Health, the team goes a step further to eradicate the threat of C. diff in the hospital and ensure that patient treatment areas are as safe and sterile as possible.

Harley knows how to sniff out C. diff spores in rooms, in hallways, and on equipment. When she detects the spores, she sits with determination. This signal tells staff where to apply extra rounds of bleach agent.

C. diff commonly is spread through fecal contamination. Harley’s ability to identify especially stubborn C. diff spores is routinely on target.

“We have tested her with about 50 different specimens, both positive and negative. She has never sat down on a known negative specimen,” said Cook, who believes Harley is currently the only dog in the United States sniffing out C. diff in a hospital.

For Vidant Medical Center, which is already ranked among the top quartile in the prevention of infection, deploying Harley is an innovative approach in its relentless pursuit of improving patient outcomes.

“Finding creative solutions to challenging problems is an important part of our mission to improve the health and well-being of eastern North Carolina. As an academic medical center, we are uniquely positioned to drive innovation alongside our partner, ECU. We are hopeful that this approach to identifying C. diff will provide a lasting solution and we are happy to support Dr. Cook, Harley and her owners as we collaboratively work toward this goal.”

Brian Floyd, president of Vidant Medical Center

Four Legs, A Tail, Many Tangible Results

According to the Mayo Clinic, most C. diff infections occur in people who are or who have recently been in a health care setting — including hospitals, nursing homes and long-term care facilities — where germs spread easily, antibiotic use is common and people are especially vulnerable to infection. In hospitals and nursing homes, C. diff is mainly transmitted on hands from person to person, but also on cart handles, bedrails, bedside tables, toilets, sinks, stethoscopes and thermometers.

Doctors have long searched for answers on how to diminish the threat of this worldwide problem. Cook’s research led him to findings from the Netherlands and Canada—where two other dogs successfully and consistently sniffed out C. diff and in turn helped improve patient outcomes.

Dr. Marije K. Bomers’ research at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam included the use of Cliff, also a beagle. Humans can sometimes detect the scent of C. diff infection, so Bomers hypothesized that a dogs’ much more keen sense of smell would be even more effective. Cliff’s precision and success rate lent hope to the hypothesis, further cemented when he identified C. diff in 25 of 30 infected patients. Cliff has since retired from his duties, but his work has started to have an international influence.

“My thought is that if they can teach a dog to sniff C. diff in the Netherlands, we should have somebody in this country that can do the same,” Cook said.

Cook contacted colleagues at ECU and Vidant Health to share context and background for the project and explore the possibility of bringing it home. Early in the process, he also reached out to get clearance from ECU’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee to ensure that Harley would being treated humanely and would not pose a health risk to people. This approval process is repeated on a yearly basis.

The project is backed financially by Vidant Health, Cook said, whose leaders were enthusiastic about the innovative and pragmatic idea.

“By positively identifying areas where C. diff is present, we are able to clean and re-clean rooms, which improves the health and safety of team members and patients. Furthermore, reduced infections mean shorter length of stays and improved experiences for those we serve.”

Dr. Keith Ramsey, chief of infection control for Vidant Medical Center.

Harley’s nose leads to shorter hospital stays and fewer infections. Her infectious smile and wagging tail brings joy and leads to patient emotional well-being, Cook said.

“My feeling is that the project pays for itself and then some by potentially reducing spread of this serious, often life-threatening infection,” Cook said. “And when we come in, everyone wants to see the dog. Everyone wants to pet her.”

In addition to the happiness and health benefits she brings to the hospital, Harley has also spurred changes to equipment sterilization protocol. Once, she detected C. diff spores lingering on an ultrasound wand after cleaning agents had been applied. In response, hospital leaders devised a new, more effective process for eradicating the bacteria without damaging the equipment.

“We instituted a policy with our medical director to clean the machine the appropriate way to kill the C. diff spores. And we would have never really thought about it if it hadn’t been for Harley.”

Jarvis Campbell, assistant nurse manager at Vidant Health

Harley’s abilities are anticipated to benefit even more patients in the future.

Read more about Harley’s background and her impeccable bedside manner.

Big Investment, Exponential Impact

With 16 public universities, each with its own research profile, North Carolina is a research and development powerhouse. UNC System institutions bring together talent, resources, and cutting edge technologies. They are ideal hubs for collaborative research, bringing together the best talent from across institutions or, in Harley’s case, non-affiliated leaders in the field.

UNC System research leads to innovative solutions to the challenges North Carolina faces, and it helps the state harness resources to capitalize on opportunities that arise. Our work doesn’t just improve the lives of the students who attend classes—it benefits every North Carolinian in some form or fashion.